A Life of Chai

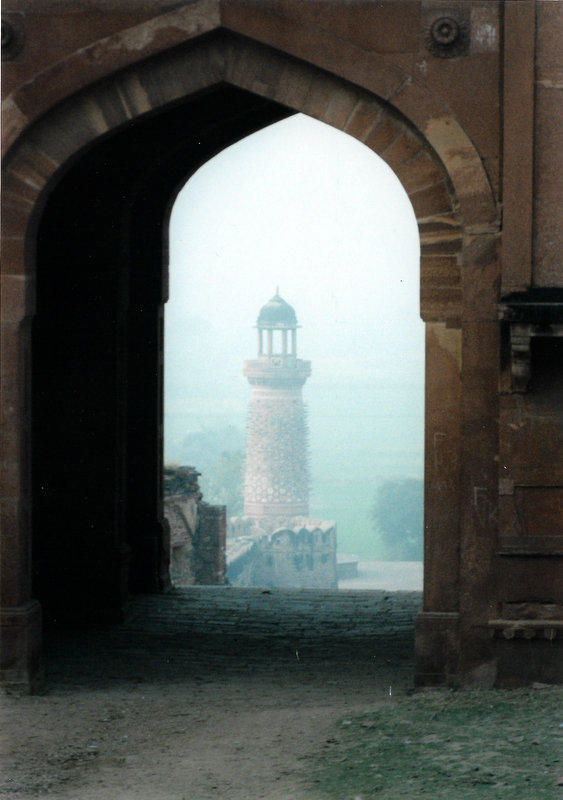

Dark side of the Red Fort, Delhi

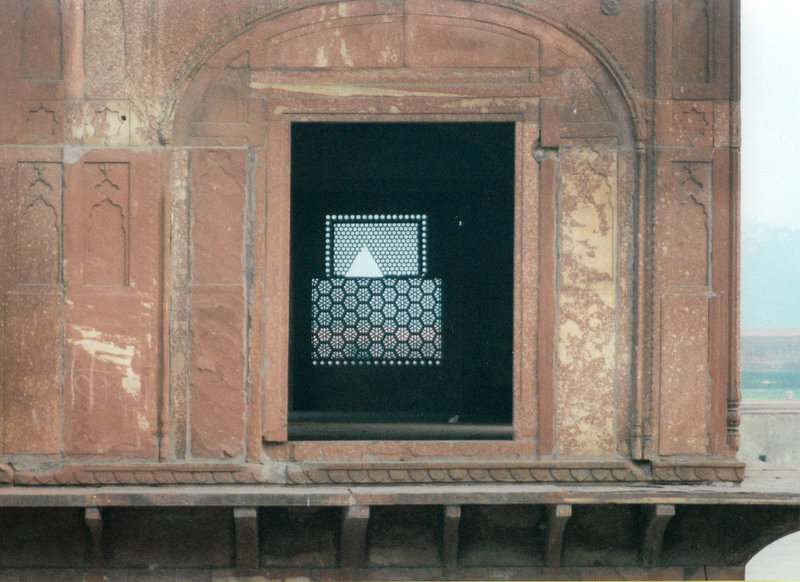

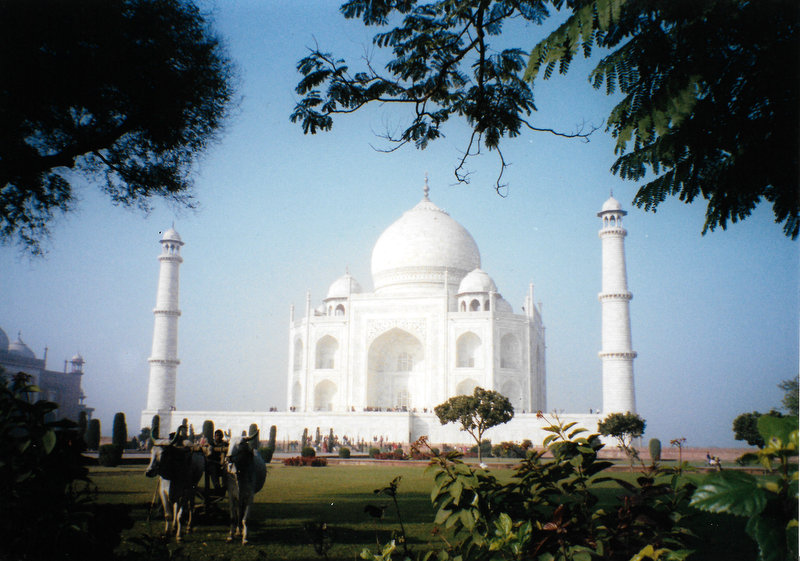

Back side of the Taj

. This is where the local Agra laundry is done, and I find myself visualising some soulless inner-city launderette, fluorescent lights, washing-powder vending machines and screeching washers with worn bearings on their last legs. I can imagine that hanging on the wall in a cobweb of lint above a stack of outdated gossip mags is a faded picture of this iconic domed mausoleum of love, a token decoration in the despair of the weekly wash. The paradox is, I’m standing at the side of an Indian launderette, dhobi wallahs with their immense workload, massive drums of dirty laundry and unfathomable filing systems. They work under the pillars of the railway bridge and are permanently in view of the real thing, and I wonder if a few of them are wishing they were in the West. Everyone wants to be somewhere else. I’m sure there is an irony there but no one is ironing here.

The elephant tower is no longer accessible, it was one of my favourite places to sit and get stoned, with my Walkman on, watching eagles circle on air currents. If you were determined you could probably climb up the protruding trunk-shaped stones that cover the outside of the tower giving it its name.

We collide with some other disreputable vehicle, it’s not a head-on collision, more a prolonged scrape of contact, a gouge where once was a dent, shining metal where once was peeling paint, the other vehicle was slower and less forceful than the one we are in so we win. We don’t stop, but the driver looks in his mirror far more frequently after the impact, I assume for cops or retribution, but we get away with it. I look at the damage when we disembark, just another day’s road scar, no one will notice.

Not so much culture differences as country differences – cities the world over have their mentality and, once left to the less fraught countryside, inevitably life becomes a bit more laid-back. This continues as we wander the narrow streets of cramped shopfronts and stalls with open sacks of peanuts and grain, all seemingly generations old, unchanged.

They still cut the grass with ox-pulled mowers, to keep the pollution of motorised vehicles from tainting the colour of the marble, a token gesture which is failing to have the desired effect.

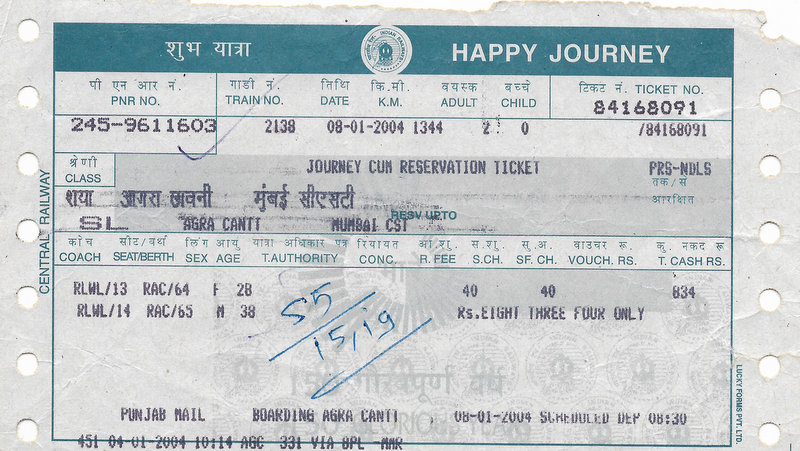

We immediately book our tickets to Bombay, which goes very smoothly until we realise we booked for the wrong day. Three more queues later, we have a ticket to ride in four days’ time.

This Gandhi bloke seems quite popular, his face is on every denomination of rupee note, so we go to the museum which is actually the house where he used to live. I’m always drawn to the bookshelf in anyone’s house, you can tell a lot about a person by the spines on display and often find some common ground too. If only I still had my copy of I’m with the Band, I could have sneaked it in between the more literary acclaimed literature. Again I’m the only one who thinks that’s funny.

Most of the doors are locked; the ones I can open reveal dark, stagnant, airless quarters with dusty transformers and generators. Someone clearly saw the benefit in transforming this area into a bedroom to generate some rent. It doesn’t quite have the seduction of the suite I booked in Delhi but there is an alluring, sleazy depravity about the place.

We even sit and watch a cricket match being played in the sprawling grounds of the old high court, built in an English Gothic style but shaded by palm trees as opposed to conifers. It’s breathing spaces like this that make a city less tiresome.

We continue to wander past what was formally known as Victorian Gothic architecture and now dubbed ‘Mumbai Gothic’, it’s better than London, the extravagance, the design, the beauty, the respect the structures are given. Nothing nasty has been crammed in next to these buildings, giving them space to show off.

The dome is a big golden EPCOT-looking thing, and actually not so different from what the Disney one originally was about: the future world. This globe being the centrepiece of Auroville (which I’ll refrain from calling a theme park) is a place of meditation and hope, so again the future world. Anyway, it’s not finished yet, planetary harmony takes time, this ‘universal township’ could accommodate 50,000 global inhabitants but actually isn’t even, after 40 years, at 10% capacity, and a third of them are native Indian.

His English is heavily accented, but not broken, the commentary well-rehearsed. ‘He is licking the nipples of her breasts, the girls are kissing each other, she is holding cocks in both hands, he is taking her from behind, she is taking the cock in her mouth, she is on her knees so she can take both …’

‘Yeah, all right, we get the visual, thanks,’ I mumble under my panting breath.

‘… and they are doing the sexy nine,’ he continues.

‘I think you mean sixty-nine,’ I find myself correcting instinctively, and then wish I hadn’t. I stop short of putting my fist in my mouth, I’m sure we’ll see something like that soon enough.

‘Yes, very sexy, and she there holds his cock as monkey flicking scrotum.’ ‘Yep, I see that now.’ Can’t say it’s a fantasy I’ve ever had but if ever there was a place … there are no shortages of monkeys here.

One of the tallest temples we see in Puri is made out of biscuits. Talk about a visionary – the Milk Bikis which are our staple choice of transit munchie have a custom-designed packet for Puri. On it is an image of the temple made out of biscuits. Power of suggestion, the resemblance is uncanny, I can’t help but wonder if a bhang lassi was involved in this inspiring marketing. The actual temple is sixty-five metres high and bows out in the middle like an urn. It’s built from layers of serrated slabs which, from a distance (and seen from a distance is our only option as non-Hindus are not allowed entry), do bear an uncanny resemblance to a pile of biscuits.

One of the wall-to-wall shops is called Pen Hospital. This to me is Indian magic – where else in the world would you find a high-street shop that specialises solely in repairing pens? I take in my Parker with its empty cartridge, depleted from describing the meeting with the Madras vagrants.

As the sky gets lighter the sights get sightier. Framed between strung-out prayer flags that are too chilled to flutter, the sun hits Kanchenjunga, the third-highest mountain in the world, and the snow on the peak glows red. Bam, got it, that’s the point of being here, the peak of perfection, the first rays of a new day projected on and reflected off of nature’s ultimate grandeur. Temperature and time go unnoticed, I’m captivated, the greatest show on earth, natural and eternal. I’m in awe.

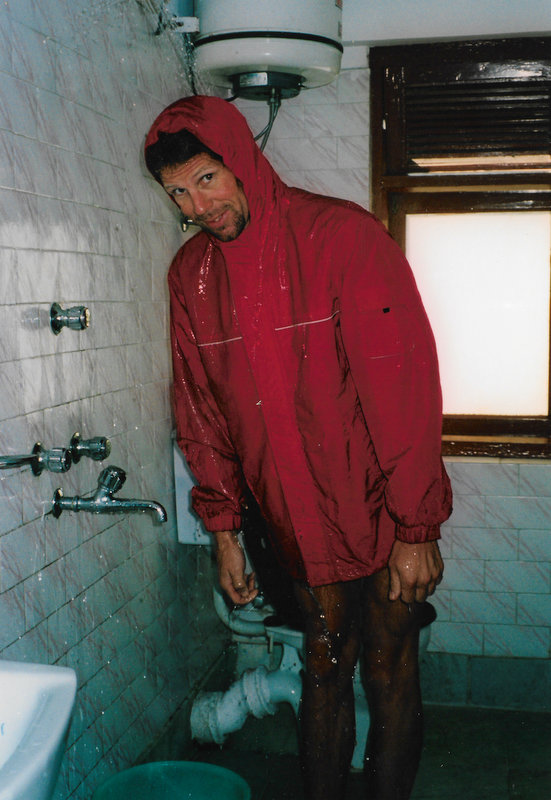

I put on my red coat and go into the shower, turn the tap on full and stand under the deluge. Yes, it is absolutely waterproof, it will be ideal for hiking Nepal. Strange behaviour? There is a method to my madness. Perhaps she should think again, are you sure you want to make a person with half a mind like mine?

Perhaps I’m repeating myself, did I mention how much I love our room? The silhouetted mountains at sunset seen from the balcony, how good it all makes me feel. Dawn and dusk will always stimulate and elate me, I just can’t say it enough – well, clearly enough for some people.

All week we’ve walked past the fried egg sandwich stand and today I stop and purchase what used to be, for me, the staple of my starving, adolescent, barely independent days. Therefore, egg in bread tastes to me like desperation, no choice, no money and I’m still hungry after I’ve eaten it. However, this one is pimped to perfection, a warmed crusty roll, onions, tomatoes, spices and condiments. I’d buy ten and take them with me if only they travelled better than a burnt-out backpacker.

At some point in time someone drew a line in the sand and declared that on each side was to be a different nationality. There will be fences, guards and regulations; documentation will be required to cross the line. The other side will be a different language, culture, currency and time; all those distinctions held back by a little line that was once nothing more than a single and uneventful step. We fill out our India exit forms and are lightened by $30 to walk into Nepal over a dry and dusty riverbed where a lone white-painted concrete marker indicates an international transition.

. The carved wooden pillars could be sanded, varnished and brought to a shine but everything is the uniform colour of air pollution, thickly coated with years of neglect. Copper pots seem popular, that’s where all the elbow polish has been deployed, they glint in the city sun, stacked, hung and perched. A variety of sizes from chai urns to bowls big enough to keep a dolphin in. These hand-beaten, glowing receptacles are a photographer’s dream, postcard potential, but there is never a break in the parade of people to capture the whole scene. Not that it matters, the passing saris, shawls and woolly hats are as much a part of this street picture as the products.

Himalayan range comes into view but the biggest rock is the star sat behind us. I leave my seat and lean over Sofia to take a photo. She can see I’m higher than the plane.

‘Focus,’ she whispers in my ear.

‘It’s automatic,’ I say.

. I feel a tap on my shoulder, a grubby little girl with a cheeky smile has climbed on the back of the rickshaw. I come back to my reality, although it’s still unsteady. She wants five rupees for a photo. I’ll pay, just to get a grip, it won’t be the best or cheapest picture in my camera but her poverty extends today’s extremes and I do want to get to the end of this film.

The clouds clear and snowy peaks come into view. They distract like nakedness. We have a chai stop which is far more refreshing and rejuvenating than I expected it to be. Stopping, it would appear, is the way forward.

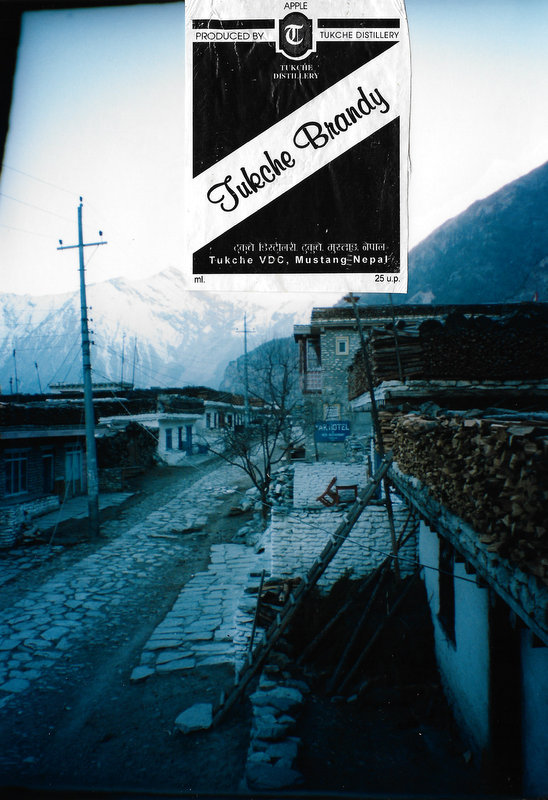

It’s a very pretty village, stepped into the hill with stone paths worn marble-smooth from the footsteps of time. The place is a resting point for packhorses, donkeys and mules – they stand in yards of drystone walls and slate roofs.

At 6 a.m. I open the shutters and watch a pink mountain cap from my sleeping bag, no sirens, no footsteps, no flicking switches, no conversation – unintelligible or otherwise – no sales pitch, no procession, no rules, no schedule, nothing but time lighting our way, this was such a good decision.

The only water supply is the other side of the path and, with toothbrush in hand, I wait by the gate as it’s rush hour. An impenetrable train of donkeys passes between me and the standpipe. It seems surprisingly normal to watch and wait for the traffic to pass, bells ringing, herder hissing and hooves thumping along the single-lane dirt track.

We go to the distillery that gave the village its name. Actually, it’s the other way round, but still I sample their entire range of offerings. Carrot, apple, apricot and peach brandy. I settle for a bottle of the latter because to my taste buds this is not brandy, it’s drinkable and for me brandy is not – unless, that is, it’s handed out for free on a plane.

The end of town, or the beginning, if you’re coming the other way, is a place of abandoned and dying donkeys, no longer useful, left for dead. Weeping sores from rubbing luggage, old or just plain knackered. Abandoned like a pair of worn-out trainers, prematurely unfit for use due to infected abrasions like scratched sunglasses. It’s a sad sight, there is no sentiment in transport that’s passed its sell-by date, but they are still living things. Is this all they have to look forward to? This is retirement, this is the end of the road once the donkey work is done. No more loads, no more trudging in a row, left for an undignified demise. I understand the hard lives of the herders, the leaders of the trains, I appreciate they can’t be expected to offer a pension or compensation plan. The donkeys are a tool of their trade and when they are no longer useful they are discarded like a blunt blade or a burned-out bulb. Whether it’s prolonging their misery or sustaining their life, we feed them some muesli bars. They seem grateful and we’re grateful our guilt is eased. Some get up, some can’t so we go to them. ‘Here, have this, you poor old thing you.

Down below is the town we fly back from. We walk into Jomsom parallel to the runway; the whole town is basically built around it.

The best views of the runway are from the toilet, I’ve had some spectacular poos with views this trip but this one is the winner. There’s more scenery that you can point a shitty stick at. I could sit here all day, almost makes me want to eat something rancid just to get my money’s worth out of this unrivalled throne.

The riverbed is supposedly littered with fossils I find one – 140 million years old, apparently. Spent its existence being brought down the riverbed, tumbled, buried, revealed, submerged, frozen, baked, and on it rolled, now to be held for the first time in the hand of a mortal.

It’s all just so vast and desolate. If you flew over this area and looked down, assuming you weren’t watching a movie, the likely comment would be, man, it’s desolate down there, and down here the same comment comes to mind.

The place has hardship written all over it and the only thing that takes archaic authenticity away are the power lines and a red sign with yellow writing saying Yak-Donald’s. It’d be funny if it weren’t such an eyesore. There is a genuine 7-Eleven sign too, not a franchise, not a shop at all really, it’s hard to say what it is, the door is locked so definitely not a 7-Eleven, I suppose they have to amuse themselves in some way.

There is a full view of Kagbeni beneath us. The residence of the riverbed, the rarest of communities, where, truly, no motorised vehicle has ever been. If one ever does, it will be a turning point, and perhaps they live in hope that tourism will be a boom for their economy – but careful what you wish for. Because it can never be changed back again, progress, like a gale blowing in your back door, only goes one way and it’s not necessarily the right direction.

The passport control is a breath of fresh air … metaphorically speaking. It’s actually a dry, dusty, piss-stinking crossing of screaming touts on both sides, attracting the attention of the human traffic that comes in every form. The two-way parade consists of native cross-border bargain shoppers, bigger business organisations and all that’s in between.

This is analogue photography, this is how it was, no instant gratification, no unlimited attempts. Film was expensive and not always the best quality, and that wasn’t evident until the photos were developed weeks later. It was a time when a view point had to be worthy of an exposure, not taking 25 selfies until the light was right and the chin defined. The photographer alone was responsible for the quality of the photo. The camera didn’t lie or enhance. ‘Washed out’ seemed to be a default setting, and it wasn’t for the developer to add tint, saturation or highlights. That was the contrast between pointing your instamatic at the admirable then, and a phone at everything now. Lives are now viewed from the other side of a digital screen with enhanced vibrancy, stored on a chip, rarely edited or reshown in an incoherence. Other that a bit of cropping here and there, I have left the photos as they appeared on the screen direct from the scanner. Keeping them as authentic as the words in the book, and there are over a quarter of a million of them because: this was a time when most memories were witnessed by the eye and retained in the mind. This page celebrates the rare occasions that were caught on film, destined to be logged chronological in a compelling file or folder, a library usually referred to as a photo album.